Wednesday, December 8, 2010

Poor Economics at OSU's Library

So I'm forced to use course reserves at Valley library. It's normally a good system except that its late charges are horribly underpriced. A buck an hour? That's ridiculous! Find me this prat whose been holding on to "Public and Private Families" for the last four hours and I will pay him oodles of cash to have this book now so I can study and go to sleep at a reasonable hour.

Valley Library needs to realize that this price is resulting in market inefficiency. Certainly the damage of this jerk holding onto the book beyond the due date is causing me more than a dollar's worth of damage. I wonder how successful a floating overdue fee would work out. I may use this excess waiting time to draft just that kind of model.

Wednesday, August 11, 2010

Credible Threats and Murdering Children

For anyone who isn't familiar with the story, back once upon a time there was a town infested with rats. The townpeople hired an expert rat-catcher to lure the vermin out of town with his magic flute. The rat-catcher did his job, but when it came time for the town to pay him, they reneged on their payment. To retaliate, the Pied Piper came back, and used his flute to lure the children of the town away and into a cave, and one can only assume he ate them all.

The moral of the story is if you don't pay the man, he'll come and take your babies from you. The fault is almost always placed on the greedy, cheating villagers and rarely on the child-killing psychopath, but my inner economists sometimes wants to side with the town.

First, let's take this incident in isolation. Granted, defaulting on promised payments can have deleterious effects on long term growth (just ask any country that's had problems repaying loans), the town could have assumed that it would be a long time before they would have another rat problem, long enough that their bad credit history with rat-catchers would have been buried with age. That's not so hard to believe, as credit agencies back in once upon a time were probably rubbish at bookkeeping, and professionals would have been starved for work anyway.

Second, no one could have predicted that the duped rat-catcher would make good on his threats. It doesn't make rational, economic sense! In game theory we learn to analyze if threats are credible. In this case, the Piper threatens to kill the town's children if he isn't paid, and that's a textbook example of a non-credible threat. If the town doesn't pay, then the Piper is left with two options: kill the kids or don't. Neither of those options will get him his money back, so at that point he would have no reason to kill the kids. Really if he were a better hostile negotiator, he would have threaten to just kidnap the kids and hold them ransom. That is a much more credible threat, and would probably have gotten him paid in the first place.

Instead the Pied Piper makes an non-credible threat, and the town rightfully called his bluff. I fully support their decision; it was just unfortunate that the Pied Piper turned out to be an irrational, child-murdering agent. Economically, the town's logic was sound, but I'll be repaying my student loans in case my creditors turn out to be as irrationally homicidal as the Pied Piper.

Sunday, July 25, 2010

Look at me, I'm reading The Economist! How reading The Economist is like drinking Indonesian cat poop coffee.

I only read three publications regularly: The Daily Barometer for its raunchy forums section, The Jakarta Post for news from Old Country, and The Economist because, as one Vanity Fair writer put it, it's "like that exotic coffee that comes from beans that have been eaten and shat out undigested by an Indonesian civet cat."

The Economist has an undeniable snob appeal, and I admit that's probably at least 50% of the reason I subscribe. One immediate indicator is its price, which has been consistently more expansive than Newsweek or Times, even after both American magazines had to update their prices due to reduced circulation. Another plus for The Economist is that its character is ostensibly that of a worldly, cynical quantitative social scientist. The magazine takes a center-right position, advocating economic liberalism, but also sensible government intervention where appropriate. These folks aren't your typical gun totting teabaggers, but you won't see them at a WTO protest either.

Lastly, The Economist insists upon itself with its cheeky petulance. Though obviously a magazine, it demands to be called a newspaper. Bylines are dropped, opting for an idea of a single, unified voice. The humor used is like an inside joke between readers and the writer. It's that kind of subtle, sarcastic wit that makes you smile smugly and go, "Heh." I bet you were beaten up a lot on the playground, too, nerd.

But while the smug appeal of The Economist might justify a slight premium, its content also excuses its price. My favorite sections of The Economist are actually its smaller articles, the ones that focus on events too local to make headlines. One article was about a woman in Washington who started a grassroots campaign to stop eminent domain, but was obstructed by bureaucratic regulations of political activism. The Economist writers often look at these minute events and interpret them from its consistent position of economism. The Economist is like that kid in your class who insists on talking about hair products from the perspective of microeconomics. You'll either hate it, or spend $120 on a yearly subscription.

Wednesday, June 30, 2010

Whoa, a thing is happening!

The real draw is that on Friday, July 2nd, our very own Patrick Emerson will be organizing and chairing a session on Issues in Growth and Development. Other celebrity panelists include Bruce McGough and Elizabeth Schroeder, who will be teaching at Oregon State starting in the Fall. Other OSU professors and grad students will also be presenting papers at the conference, so click here for more information about the conference.

Sunday, June 13, 2010

June is John Maynard Keynes Month

June 5th is the birthday of both John Maynard Keynes and Adam Smith. What an auspicious day to be an economist!

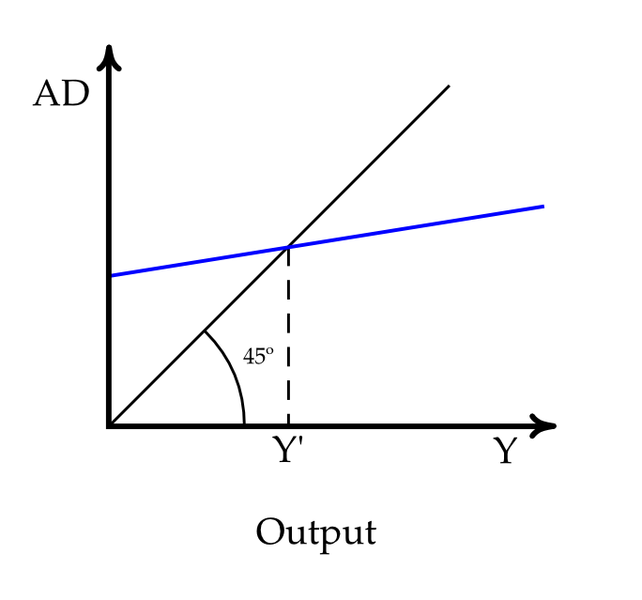

Keynes, a Depression-era macroeconomist, has come back into popular (popular for an economist) focus after this most recent economic crisis. His solution to depressed markets could be grossly simplified as fiscal expansion. If governments spend more, total output will increase.

In fact, looking at the Keynesian Cross model, even a modest increase in aggregate demand will lead to a much larger boost in output. The story is delightfully simple. Imagine today the government gives you 10 bucks to build a dam. You take that 10 bucks, save maybe 2 dollars, and spend the other 8 on Carls Jr. Carl then takes your 8, saves a dollar from it, and spends the other 7 buying more beef. The rancher saves a bit, spends the rest on fertilizer, and so on and so on. We see that from that initial 10 dollars, the money goes a long way in generating transactions.

Of course we learn this the first week of Intermediate Macroeconomics I. Week two, with its IS-LM and A Sad World models, shows us why this doesn't work and why we should all be good little monetarists. Still, enjoy your time in the sun, Mr. Keynes! June is your month!

Last thing I want to share, hip hop artist Slim Thug giving props to Sir John. Skip to 1:40 for the coolest moment macroeconomics will ever have.

| The Daily Show With Jon Stewart | Mon - Thurs 11p / 10c | |||

| Slim Thug's Music Video - Still a Boss | ||||

| www.thedailyshow.com | ||||

| ||||

Wednesday, June 2, 2010

Seminar! Seminar!

Tuesday, May 25, 2010

Thinking about Grad School? Me neither!

My favorite tidbit is: "Get to know some professors well. Professors will be very excited that you want to get a Ph.D. in economics. Don't be afraid to approach them. Listen to their advice."

In other words, come to the econ club meetings more often! Get to know the professors better, gamble on whether they'll pay for the food, and banter nonsensically about things tangentially related to economics!

Tuesday, May 4, 2010

That's the beauty of it - it doesn't do anything!

Lately some econ buddies and I have discovered that we really don't know how to define exactly what economics is. You know when you're in an econ class, but why exactly is uncertain. Vaguely it has something to do with limited supply and infinite demand. The solution is always where marginal benefit equals marginal cost. There damn well better be some calculus in it at some point.

So we have a laundry list of "You know you're in an econ class when..." but no real answer as to what economics is. My peers have been offering me some really neat explanations, but I prefer to pound economics into two realizations:

1. Economics is life sans bullshit.

Every important facet of human life will eventually be studied by an economist, and they will strip it down to its integral parts. While most people have some misguided notion that econ students study the stock market all day, anyone who has sat through Prof. Grosskopf's efficiency class and has listened to students' research proposal knows that economics studies everything imaginable. Some people are studying airports. I'm looking at tobacco ads. A bunch of guys are doing baseball. People who have never opened an econ journal or read Freakonomics might be puzzled to see the scope economists encompass. Economics is varied and everywhere.

More importantly, economics does away with the bullshit that accrues when other fields study issues. Sit in on a business class and listen to them talk about value. For them, value = quality / price. What is quality? Personal value to customer. How is that different from the value on the left side of the equation? Hell if I know, because to an economist, value = price you're willing to pay. Bam. Simple.

Here's another example. Ask a person what goes into their decision to buy goods. They might go on all day about why this product is good, why this one's a bargain, why these ones are crap, why they're addicted this those, etc etc. To an economist, it's just Dx(Px, Py, I) Booya, a demand function.

Economics takes a subject and does away with the frills, gimmicks, and buzzwords. What's left is what's essential. There is a methodical, mathematical cleanliness to economics that you just won't get from other social sciences or business disciplines. If there is a relentless difficulty to economics, it's because you cannot escape it with bullshit.

Which leads me to my second conclusion:

2. The World operates on bullshit.

My econ degree makes me feel helpless and frustrated. Economists know the answer. Fiscal policy is ineffective in the medium run. Externalities can be solved with the Coase solution. Businesses should operate until marginal cost equals marginal benefit. There are no profits in the long run.

So why the hell do I find myself arguing with the newspaper every morning? Why are politicians doing silly things, and why can't I get a job after graduating? I can only conclude that this is because the world actually operates on bullshit. All the useless variables I've spent my education learning to assume away is actually the most important part of the function.

It turns out, kiddos, that you won't be paid the marginal product of your labor; it's who you know. Politicians will whimsically order some parts of your life and not others. Businesses actually want you to use buzzwords. You will not need calculus.

It's a rather cynical conclusion. Studying econ has told me that economics is right, but ignored and possibly useless. We come after the fact, so some other discipline will come up with a new idea, and economists can explain why is succeeded or failed. Getting people to listen to our own ideas, or maybe even just coming up with original ideas on our own, is a harder, meaner feat.

I'm hoping to be proved wrong, though, and I heard someone in our department recently got an internship with the Fed, so there might be hope yet. Also they keep telling me that economics majors make money after college, so maybe there is a demand for less bullshit.

May is Karl Marx Month

Cinco de Mayo, more than just a Mexican holiday, is also the birthday of Karl Marx, notorious political economist and Evil Santa Look-a-like. When I was in the 10th grade, we had to read the Communist Manifesto for an English class. At the time, I was also working in retail and a member of a union, UFCW Local Chapter 555, so it was an exciting time to be a budding communist.

Then I took 11th grade Economics and promptly forgot about class struggles and command economies. Looking back, I wonder how communist economics would be taught in a true econ class using models and mathematics instead of just rhetoric. It's too bad Oregon State doesn't offer a course on heterodoxical economic models.

May is an important month for working people. May 1st is International Workers' Day, when unions and left-wing political groups take to the streets and protest for better living standards for the working class. Even though May Day started in Chicago, it has lost popularity. in America. Labor demonstrations remain very aggressive in the rest of the world, with protests turning violent in cities such as Athens, Macau, and Berlin.

Karl's grim specter of Communism hasn't completely left the world even after the end of the USSR. Workers around the world have yet to buy into free market liberalism and remain skeptical of its promises. Although I haven't been an active member of my union in years, I'm going to make an effort to wear red this month to show at least superficial camaraderie for my working brothers and sisters.

Saturday, April 24, 2010

Natural Level of Output: A less-than-sober argument

Fellow economics major Ben Price and I got in an argument about medium-run macroeconomics. I've heard macroeconomics called a moon science by other econ majors around the country, but I still accept that these are the best models we have at describing the macroeconomy. At the very least, they're worthwhile classes that I enjoy occasionally being awake in.

Ben, my esteemed interlocutor, disagrees more intensely about the assumptions of macroeconomics. Today, after a few beers and Cuba Libres, Ben challenged the idea of a natural level of output, which Oliver Blanchard identifies as that level of output economies return to after a change in fiscal or monetary policy. Ben demanded proof of such a natural rate, asking for real world data that I usually find distracting and unimportant to economics.

For me, the intuition behind a natural level of output is solid. Imagine a simplified economy where all people did was pick bananas all day. There is a limit to how many bananas can be picked, and that limit is hard to change. We can only be so efficient at banana picking. A government can come in and try to tinker with our output, telling us there's more hours in a day, or inflating the value of a banana to encourage us to work harder, but these are short run solutions. In the end, our bodies are only so good at picking bananas.

A macroeconomic natural level of output figures in the same way. Economies can only be so productive before artificial means of accelerating an economy such as expansionary monetary or fiscal policies only provide short run gains. In the medium run, when people can adjust price expectations and therefore reevaluate the values of goods, economies return to their natural levels.

Makes sense, right? Of course, I don't feel the need to prove any of this with data. It's a moon science!

Wednesday, April 21, 2010

Facebook Page

I have also created one for the Economics Deparment, so join that as well.

Fat Kow, Monopolistic Competitition, and College Diet

The econ kids were talking about how come we don't see more of these food carts in Corvallis. Econ undergrads are notoriously price sensitive (this is why we meet in a bar during happy hour), but there is also a genuine economic intuition behind our curiosity.

Restaurants generally fall under the microeconomic umbrella of monopolistic competition. Like perfect competition, there are many firms and few barriers to entry. But like monopolies, restaurants have a degree of market power and product differentiation. Still, in the long-run, monopolistic competitors should find themselves producing zero economic profits, as any profit should be eaten away by new firms entering the market.

The introduction of food carts has the potential to upset the status quo, as they are generally regarded to have a lower average cost than restaurants. No wait staff, no building costs, and low maintenance needs all might drive costs down enough to seriously change the food game. Restaurants will still serve a purpose; you could probably never bring a date to a food cart unless you both are exceptionally open-minded. But for those quick and cheap dashes for food in between classes, food carts might finally break Carl's Jr.'s $1 spicy chicken dominance over the market.

But while my econ buddies were optimistic about the future of food carts on campus, I was personally hesitant. Thanks to my rigorous theoretical education from Professor McGough, I am now convinced that there are no more good ideas left in the world. If campus food carts are such a lucrative venture, why haven't more entrepreneurs taken up the gauntlet? There must be a reason, maybe some rule banning food carts that the University heads and the angry Panda Express lady cooked up in a back room a few years back. I'm just too pessimistic to believe that a few tipsy undergrads can come up with an original business plan someone else hasn't already tried and failed.

Then again, if I thought I could make money, I'd probably be inside Bexell rather than outside eating savory tofu and garbanzo beans.

Tuesday, April 20, 2010

Boom, Bust, Wicka Wicka

I'm not a big fan of ironic white hip hop, but this video is too important to ignore. It's only in times like these that macroeconomics gets any love. Still, the video focuses on Keynes and Hayek, but ignores Friedman? I'm guessing they're waiting for a sequel where Milton does a drive-by on these fools. And then maybe Blanchard can do a tender folksy acoustic cover.

Next time I'll have a video of a real hip hop artist giving love for expansionary fiscal policy. Or maybe I'll go back to actually talking about economics. Won't that be a treat!

Saturday, April 17, 2010

Broadway does Economics

The story has a lot of complicated financial gobbledygook, but the intuition is pretty simple. Magnetar bought a bunch of risky housing assets, knowing they were risky. But instead of expecting big returns for big risk, Magnetar had a different plan. They took out insurance on these assets in the form of Credit Default Swaps, hoping that the assets fail and Magnetar can collect massive profits from their insurance payoffs. Well, it worked. The company made record profits buying garbage assets, and thus laid the groundwork for a financial collapse.

It sounds like insurance fraud to me, but Alex made a more comical connection. Ever seen The Producers? In that musical, two Broadway producers realize they can make oodles of money by overselling shares on a play they plan to make terrible. NPR takes the analogy a step further by parodying one of The Producers' song in this humorous and informative number:

'Bet Against The American Dream' from Planet Money on Vimeo.

Pretty good stuff, right? Almost as good as this macroeconomics gangster rap I'll be sharing next time. Stay tuned!

Wednesday, April 14, 2010

Last on his list, first in his heart.

Thursday, April 8, 2010

Another Meeting and Some Things I Think About In Class

Speaking of diminishing marginal returns, that has to be one of my favorite concepts in Economics. Econ professors like to joke during a long afternoon class that they can definitely see evidence of downward sloping marginal benefits when their students start napping, getting off-topic, and daydreaming out the window. Of course, professors from other departments must also be aware of the gradual decline in focus over the course of a long lecture, but I wonder if economists take less offense to it. I sure hope so because sleeping in class gives me wicked awesome dreams.

Thursday, February 25, 2010

A meeting today!

Monday, February 22, 2010

Should I split or should I steal?

Aside from always sounding prim and intelligent, the Brits also have a knack with game shows. They invented Who Wants to Be A Millionaire and Deal or No Deal. Right now I'm hooked on one that hasn't made its way across the Pond, called Golden Balls.

The interesting part about Golden Balls is the way every game ends. It starts out with two random players working together to build up a pot of money. It's pretty much a lottery game up until the end, where the add an element of game theory, and my econ senses tingle. Anyone who knows the Prisoner's Dilemma will find it familiar.

After the jackpot is final, each player gets to choose whether they will split or steal the pot. If both choose split, each one gets 50% of the pot. If one steals while the other splits, the thief gets all. If both try to steal, though, they both walk away with nothing. There is discussion before hand, but both players must announce their decision before hands.

All good economists know the Nash equilibrium. Both should decide to steal, and walk away with nothing. Sometimes this happens, but sometimes not. Sometimes, a little miracle happens and both choose split and both hug each other and even in me, a little part thinks I have it all wrong about how cruel and evil the world is. Sometimes, a good soul chooses split while the partner chooses steal, and I feel the loser will go on to be a cynical economist.

This game does break the standard prisoner's dilemma because the agents can communicate and collude. Real life prisoners have done the same thing by forming criminal organizations that have oaths of silence. Suddenly a little bit more jail time doesn't sound so bad when faced with having your loved ones killed by vengeful gangsters. Morality and social pressure work in similar ways. The crowd cheers when the partners reach a split-split decision, and boo when someone steals. Is that extra cash worth being televised as a jerk?

So what would you do? Split or steal? Personally I would split, but only because I'd be diversifying my risk. If my partner splits, I walk out with money and a sense of human progress. If my partner steals, at least I'll be assured that I did not make a mistake in studying the dismal science of economics.

Wednesday, February 10, 2010

Keeping up with the Joneses

Thursday, February 4, 2010

February is Edgeworth Month

Frank is famous for giving us the Edgeworth Box, one of my favorite economics gizmos. Aside from having fistfuls of innuendos shoved into every crack, the Edgeworth Box combines mathematical economics with the more talking-points economics (my personal favorite). An Edgeworth Box is great for demonstrating the first two fundamental theorems of welfare economics. The first theorem tells us that if certain conditions are met, self-serving agents will naturally come to a socially optimal outcome. The second tells us that by manipulating initial endowments, any socially optimal point is accessible.

What does this mean for the pundit economist? It means we should emphasize trade, trade, trade. Governments should establish property rights and allow individuals to exchange goods, and all parties will be better off. This sort of mutual benefaction is a good counter against those who are cautious about capitalism and see it as a zero-sum game.

There's some calculus in the Edgeworth Box which will not doubt please the more mathematically inclined econ student, but most of its concepts can also be demonstrated visually with some curves and lines. Overall, it's one of the sexiest things I've ever seen in my life.

Saturday, January 30, 2010

Cynicism and the Science of Poverty Reduction

Elizabeth Schroeder came by Oregon State yesterday to give a lecture on the efficacy of microfinance. For those who don't know, microfinance is a lending system used in developing countries where normal credit markets don't exist. Lending is a pretty hard thing to do in the long run. Imagine people came up to you and asked to borrow some money with interest. Would you do it? You might if they appeared wealthy, gave collateral, and had good references. Those don't necessarily exist in the developing world. Banks understand the same thing.

This can be damning for poor communities. Starting even a simple business can have substantial start-up costs, which become problematic barriers without lending. Wealthy nations also suffer. Our simplest economic models tell us that you can get a lot of bang from your first bucks invested than from your billionth, and yet capital is not flowing into these economies of great potential. The uncertainty is just too great for traditional financial systems, even though there is money to be made in the developing world.

Enter microfinance. In this system, you, the lender, still don't know much about your clients in the developing world, but those potential borrowers probably know a bit about each other. They have friends just like everyone else, and they gossip and pry and quietly judge one another just like you. It's simple, then. Offer individual loans, but only to people who have formed a group of five other interested borrowers. If anyone in the group defaults, you cut credit off to everyone in the group. What happens is that people will only invite into a group friends who they trust not to default. As an added bonus, you might even get a little social pressure on deadbeat debtors to make their payments, and you don't spend a dime on collection agencies.

There's money to be made in these lending groups. The average interest rate is around 20%, while the repayment rate is an impressive 90%. It doesn't take a finance major to see the profit in microfinance. Oh yeah, you're also helping the poor of the world (as Ms. Schroeder demonstrated in her paper), but it's an example of cold economics turning the gears and not high-minded idealism. Bankers want to make money, struggling entrepreneurs will self-select, the incentives are there, and everyone is made better off.