While looking at my loan repayment plan today, I started thinking about the fairy tale of the Pied Piper.

For anyone who isn't familiar with the story, back once upon a time there was a town infested with rats. The townpeople hired an expert rat-catcher to lure the vermin out of town with his magic flute. The rat-catcher did his job, but when it came time for the town to pay him, they reneged on their payment. To retaliate, the Pied Piper came back, and used his flute to lure the children of the town away and into a cave, and one can only assume he ate them all.

The moral of the story is if you don't pay the man, he'll come and take your babies from you. The fault is almost always placed on the greedy, cheating villagers and rarely on the child-killing psychopath, but my inner economists sometimes wants to side with the town.

First, let's take this incident in isolation. Granted, defaulting on promised payments can have deleterious effects on long term growth (just ask any country that's had problems repaying loans), the town could have assumed that it would be a long time before they would have another rat problem, long enough that their bad credit history with rat-catchers would have been buried with age. That's not so hard to believe, as credit agencies back in once upon a time were probably rubbish at bookkeeping, and professionals would have been starved for work anyway.

Second, no one could have predicted that the duped rat-catcher would make good on his threats. It doesn't make rational, economic sense! In game theory we learn to analyze if threats are credible. In this case, the Piper threatens to kill the town's children if he isn't paid, and that's a textbook example of a non-credible threat. If the town doesn't pay, then the Piper is left with two options: kill the kids or don't. Neither of those options will get him his money back, so at that point he would have no reason to kill the kids. Really if he were a better hostile negotiator, he would have threaten to just kidnap the kids and hold them ransom. That is a much more credible threat, and would probably have gotten him paid in the first place.

Instead the Pied Piper makes an non-credible threat, and the town rightfully called his bluff. I fully support their decision; it was just unfortunate that the Pied Piper turned out to be an irrational, child-murdering agent. Economically, the town's logic was sound, but I'll be repaying my student loans in case my creditors turn out to be as irrationally homicidal as the Pied Piper.

Wednesday, August 11, 2010

Sunday, July 25, 2010

Look at me, I'm reading The Economist! How reading The Economist is like drinking Indonesian cat poop coffee.

I only read three publications regularly: The Daily Barometer for its raunchy forums section, The Jakarta Post for news from Old Country, and The Economist because, as one Vanity Fair writer put it, it's "like that exotic coffee that comes from beans that have been eaten and shat out undigested by an Indonesian civet cat."

The Economist has an undeniable snob appeal, and I admit that's probably at least 50% of the reason I subscribe. One immediate indicator is its price, which has been consistently more expansive than Newsweek or Times, even after both American magazines had to update their prices due to reduced circulation. Another plus for The Economist is that its character is ostensibly that of a worldly, cynical quantitative social scientist. The magazine takes a center-right position, advocating economic liberalism, but also sensible government intervention where appropriate. These folks aren't your typical gun totting teabaggers, but you won't see them at a WTO protest either.

Lastly, The Economist insists upon itself with its cheeky petulance. Though obviously a magazine, it demands to be called a newspaper. Bylines are dropped, opting for an idea of a single, unified voice. The humor used is like an inside joke between readers and the writer. It's that kind of subtle, sarcastic wit that makes you smile smugly and go, "Heh." I bet you were beaten up a lot on the playground, too, nerd.

But while the smug appeal of The Economist might justify a slight premium, its content also excuses its price. My favorite sections of The Economist are actually its smaller articles, the ones that focus on events too local to make headlines. One article was about a woman in Washington who started a grassroots campaign to stop eminent domain, but was obstructed by bureaucratic regulations of political activism. The Economist writers often look at these minute events and interpret them from its consistent position of economism. The Economist is like that kid in your class who insists on talking about hair products from the perspective of microeconomics. You'll either hate it, or spend $120 on a yearly subscription.

Wednesday, June 30, 2010

Whoa, a thing is happening!

If you're in Portland from now until July 3rd, the 85th annual conference of the Western Economic Association International is meeting to talk econ things and do econ stuff, which I think means drinking, a great tradition I'm proud our econ club follows. The registration fee is outrageous, but someone in our department told us you can sneak in real easy. It'll be like jumping the fence at Coachella, except a lot less cool.

The real draw is that on Friday, July 2nd, our very own Patrick Emerson will be organizing and chairing a session on Issues in Growth and Development. Other celebrity panelists include Bruce McGough and Elizabeth Schroeder, who will be teaching at Oregon State starting in the Fall. Other OSU professors and grad students will also be presenting papers at the conference, so click here for more information about the conference.

The real draw is that on Friday, July 2nd, our very own Patrick Emerson will be organizing and chairing a session on Issues in Growth and Development. Other celebrity panelists include Bruce McGough and Elizabeth Schroeder, who will be teaching at Oregon State starting in the Fall. Other OSU professors and grad students will also be presenting papers at the conference, so click here for more information about the conference.

Sunday, June 13, 2010

June is John Maynard Keynes Month

June 5th is the birthday of both John Maynard Keynes and Adam Smith. What an auspicious day to be an economist!

Keynes, a Depression-era macroeconomist, has come back into popular (popular for an economist) focus after this most recent economic crisis. His solution to depressed markets could be grossly simplified as fiscal expansion. If governments spend more, total output will increase.

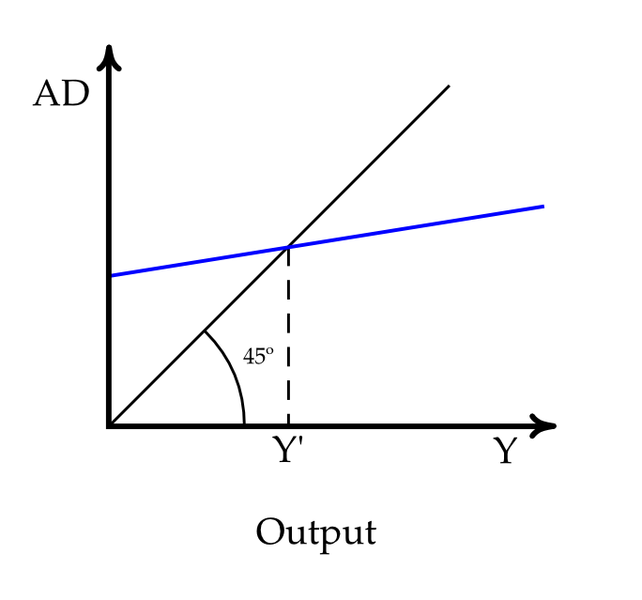

In fact, looking at the Keynesian Cross model, even a modest increase in aggregate demand will lead to a much larger boost in output. The story is delightfully simple. Imagine today the government gives you 10 bucks to build a dam. You take that 10 bucks, save maybe 2 dollars, and spend the other 8 on Carls Jr. Carl then takes your 8, saves a dollar from it, and spends the other 7 buying more beef. The rancher saves a bit, spends the rest on fertilizer, and so on and so on. We see that from that initial 10 dollars, the money goes a long way in generating transactions.

Of course we learn this the first week of Intermediate Macroeconomics I. Week two, with its IS-LM and A Sad World models, shows us why this doesn't work and why we should all be good little monetarists. Still, enjoy your time in the sun, Mr. Keynes! June is your month!

Last thing I want to share, hip hop artist Slim Thug giving props to Sir John. Skip to 1:40 for the coolest moment macroeconomics will ever have.

| The Daily Show With Jon Stewart | Mon - Thurs 11p / 10c | |||

| Slim Thug's Music Video - Still a Boss | ||||

| www.thedailyshow.com | ||||

| ||||

Wednesday, June 2, 2010

Seminar! Seminar!

Our very own Zheng Cao and Daniel Stone will be presenting a paper on choking under pressure in the NBA this Friday, 1pm in Kelley 1001. You're all welcome to come and show support and pretend you understand economics for a while until the speakers get to the punchy conclusion. Afterwards we may have an econ club meeting to elect the new president, or I'll just assume power.

Tuesday, May 25, 2010

Thinking about Grad School? Me neither!

But in case you decide 3 more years of sadness is in your future, an anonymous senior level cabinet official professor from the department linked me to this page full of advice on applying to grad school.

My favorite tidbit is: "Get to know some professors well. Professors will be very excited that you want to get a Ph.D. in economics. Don't be afraid to approach them. Listen to their advice."

In other words, come to the econ club meetings more often! Get to know the professors better, gamble on whether they'll pay for the food, and banter nonsensically about things tangentially related to economics!

My favorite tidbit is: "Get to know some professors well. Professors will be very excited that you want to get a Ph.D. in economics. Don't be afraid to approach them. Listen to their advice."

In other words, come to the econ club meetings more often! Get to know the professors better, gamble on whether they'll pay for the food, and banter nonsensically about things tangentially related to economics!

Tuesday, May 4, 2010

That's the beauty of it - it doesn't do anything!

Lately some econ buddies and I have discovered that we really don't know how to define exactly what economics is. You know when you're in an econ class, but why exactly is uncertain. Vaguely it has something to do with limited supply and infinite demand. The solution is always where marginal benefit equals marginal cost. There damn well better be some calculus in it at some point.

So we have a laundry list of "You know you're in an econ class when..." but no real answer as to what economics is. My peers have been offering me some really neat explanations, but I prefer to pound economics into two realizations:

1. Economics is life sans bullshit.

Every important facet of human life will eventually be studied by an economist, and they will strip it down to its integral parts. While most people have some misguided notion that econ students study the stock market all day, anyone who has sat through Prof. Grosskopf's efficiency class and has listened to students' research proposal knows that economics studies everything imaginable. Some people are studying airports. I'm looking at tobacco ads. A bunch of guys are doing baseball. People who have never opened an econ journal or read Freakonomics might be puzzled to see the scope economists encompass. Economics is varied and everywhere.

More importantly, economics does away with the bullshit that accrues when other fields study issues. Sit in on a business class and listen to them talk about value. For them, value = quality / price. What is quality? Personal value to customer. How is that different from the value on the left side of the equation? Hell if I know, because to an economist, value = price you're willing to pay. Bam. Simple.

Here's another example. Ask a person what goes into their decision to buy goods. They might go on all day about why this product is good, why this one's a bargain, why these ones are crap, why they're addicted this those, etc etc. To an economist, it's just Dx(Px, Py, I) Booya, a demand function.

Economics takes a subject and does away with the frills, gimmicks, and buzzwords. What's left is what's essential. There is a methodical, mathematical cleanliness to economics that you just won't get from other social sciences or business disciplines. If there is a relentless difficulty to economics, it's because you cannot escape it with bullshit.

Which leads me to my second conclusion:

2. The World operates on bullshit.

My econ degree makes me feel helpless and frustrated. Economists know the answer. Fiscal policy is ineffective in the medium run. Externalities can be solved with the Coase solution. Businesses should operate until marginal cost equals marginal benefit. There are no profits in the long run.

So why the hell do I find myself arguing with the newspaper every morning? Why are politicians doing silly things, and why can't I get a job after graduating? I can only conclude that this is because the world actually operates on bullshit. All the useless variables I've spent my education learning to assume away is actually the most important part of the function.

It turns out, kiddos, that you won't be paid the marginal product of your labor; it's who you know. Politicians will whimsically order some parts of your life and not others. Businesses actually want you to use buzzwords. You will not need calculus.

It's a rather cynical conclusion. Studying econ has told me that economics is right, but ignored and possibly useless. We come after the fact, so some other discipline will come up with a new idea, and economists can explain why is succeeded or failed. Getting people to listen to our own ideas, or maybe even just coming up with original ideas on our own, is a harder, meaner feat.

I'm hoping to be proved wrong, though, and I heard someone in our department recently got an internship with the Fed, so there might be hope yet. Also they keep telling me that economics majors make money after college, so maybe there is a demand for less bullshit.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)